The Church’s saints were not canonized because they lived flawless lives. Many of them fell deeply—into addiction, violence, sexual sin, pride, greed, spiritual confusion, or despair. What makes them saints is not a perfect past, but a radical openness to God’s mercy.

Scripture reminds us, “Where sin increased, grace abounded all the more” (Romans 5:20). The saints are living proof that this is not just theology—it is reality.

Their stories dismantle a common lie: that holiness is only for the morally consistent or spiritually strong. Instead, the saints show us something far more hopeful: conversion is possible for anyone.

What Does It Mean to Be Transformed in Faith?

Transformation in faith is not self-improvement. It is conversion of heart—a turning away from sin and a turning toward God, often through struggle, suffering, and surrender.

God promises, “I will give you a new heart and place a new spirit within you” (Ezekiel 36:26). Sometimes that transformation is sudden. More often, it is slow, hidden, and costly. But grace always works in truth.

St. Augustine of Hippo

Sexual Addiction, Pride, and Control → Surrender of the Will

Augustine’s sins were not hidden. He openly admitted to sexual addiction, describing how lust ruled his decisions and imagination. He kept a concubine for over a decade, refusing marriage because he feared losing pleasure and autonomy. He fathered a child outside marriage and treated women as emotional dependencies rather than persons.

Alongside lust, Augustine battled intellectual pride. He believed Christianity was too simple for someone of his intelligence. He mocked the faith publicly while privately fearing that it might be true.

His conversion did not begin with holiness—but with exhaustion. He wanted chastity, but only later. He wanted truth, but without obedience. Finally, when he heard the words “Take and read,” he opened Scripture to “Put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh” (Romans 13:13–14).

This was not a gentle invitation—it was a command that confronted his specific sins. Augustine wept, surrendered his will, and chose celibacy, humility, and obedience.

Grace did not erase his past; it reordered his desires. The man enslaved to lust became a teacher of freedom.

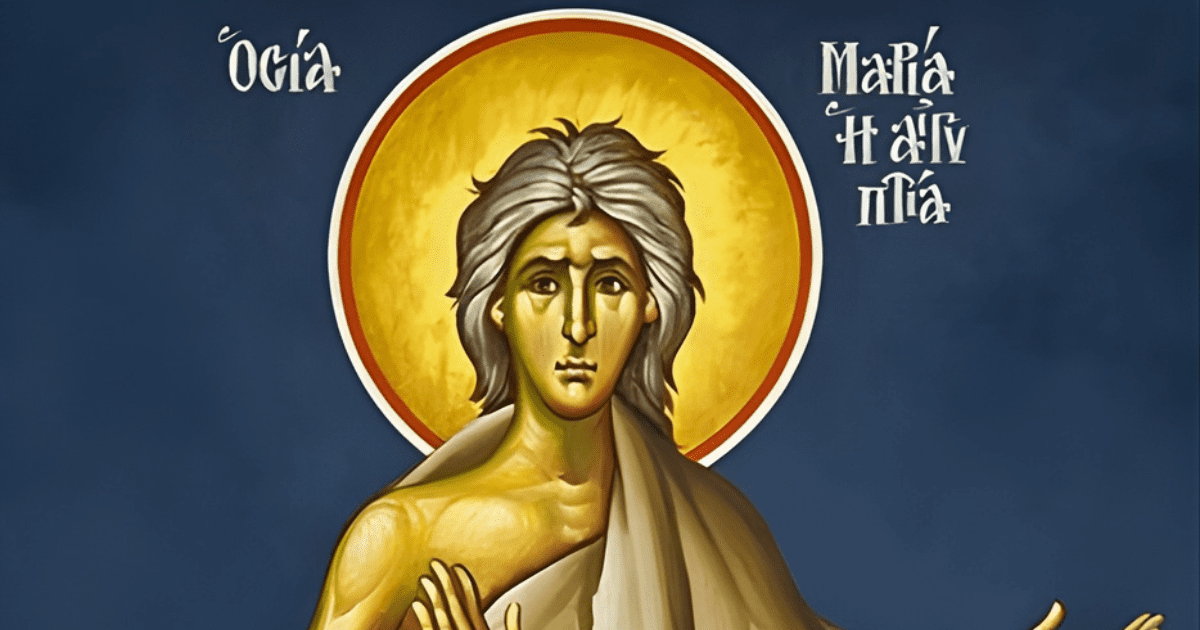

St. Mary of Egypt

Compulsive Sexual Sin → Radical Renunciation

Mary of Egypt lived in deliberate, compulsive sexual sin from a young age. She did not sell herself out of poverty—she pursued pleasure intentionally, boasting that she seduced others for enjoyment.

Her conversion began not with guilt but with spiritual resistance. When she attempted to enter a church, an unseen force prevented her. For the first time, she recognized that her sin had hardened her heart.

Mary did not bargain with God. She renounced her former life completely, crossed the Jordan River, and entered the desert with almost no provisions. There, she battled intense physical cravings, memories, and loneliness for years.

Her holiness was not instant peace but endurance. She lived the truth of “Go, and sin no more” (John 8:11) by cutting herself off from every former pattern of sin.

Mary shows us that conversion may require radical separation from what once defined us.

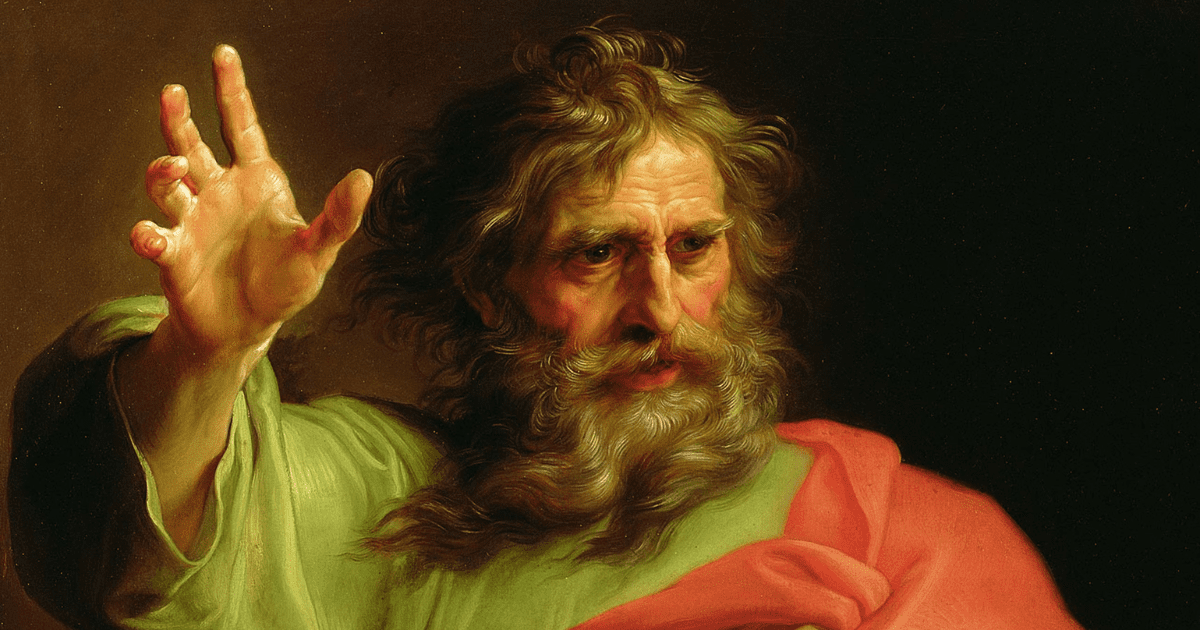

St. Paul the Apostle

Religious Violence and Self-Righteousness → Humble Dependence

Paul’s sin was not immorality—it was self-righteous violence. Convinced he was defending God, he approved of executions, imprisoned Christians, and hunted believers.

His conversion was humiliating. Christ blinded him, stripping him of control, reputation, and certainty. Paul had to be led by the hand and taught by those he once despised.

Paul never minimized his past. He called himself “the foremost of sinners” (1 Timothy 1:15). Yet grace redirected his intensity toward sacrificial love.

His story teaches us that being sincere does not mean being right—and that God sometimes dismantles our confidence before rebuilding our mission.

St. Ignatius of Loyola

Vanity, Lustful Fantasy, and Ambition → Interior Discipline

Ignatius’ sins lived largely in his imagination. He indulged in fantasies of romance, honor, and admiration. Even after being wounded, he replayed these desires endlessly.

His conversion came through self-observation. He noticed that sinful fantasies left him restless, while thoughts of Christ brought peace. This interior struggle became the foundation of spiritual discernment.

Ignatius did not suppress desire—he trained it. He subjected imagination, ambition, and ego to prayer and discipline, teaching others to do the same.

His conversion shows that sin is not only about actions, but about where the heart dwells.

St. Mark Ji Tianxiang

Addiction, Shame, and Sacramental Deprivation → Faith Without Consolation

Mark Ji Tianxiang became physically addicted to opium, a dependency not fully understood in his time. His addiction brought shame and exclusion.

Denied the sacraments for nearly 30 years, Mark endured what many would consider unbearable: prayer without consolation, faith without reassurance.

He did not relapse spiritually. He prayed daily, attended Mass, and trusted God in silence. His martyrdom revealed what had been hidden all along: perseverance itself had sanctified him.

Mark teaches us that holiness is sometimes faithfulness without relief.

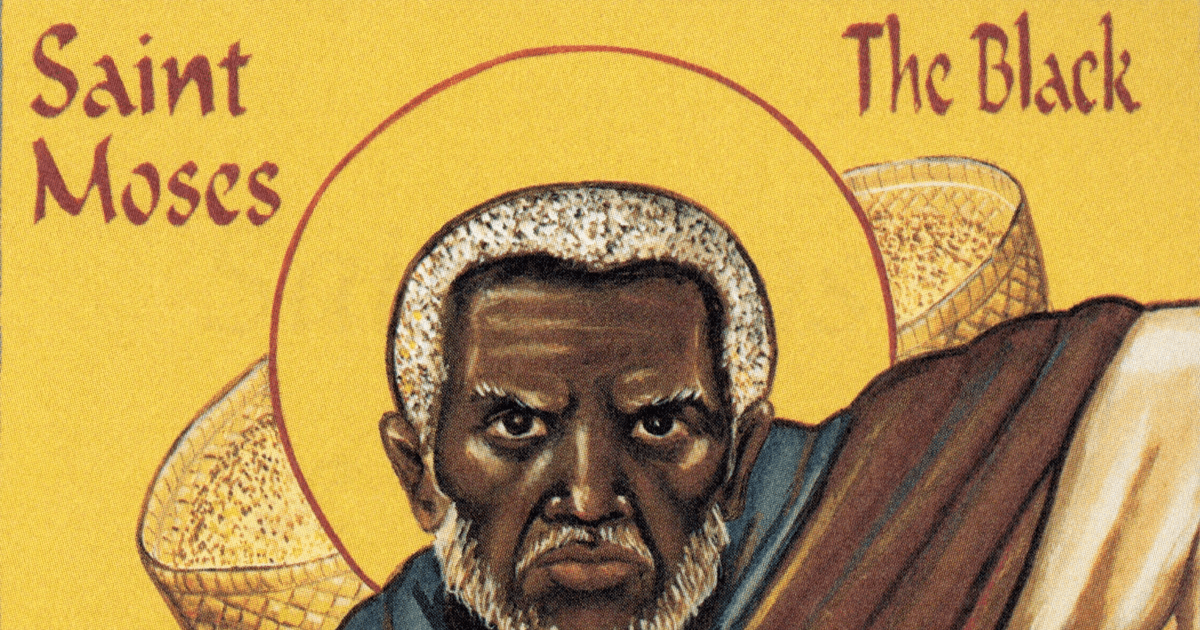

St. Moses the Black

Violence, Theft, and Rage → Radical Humility

Moses lived by fear and force. He stole, killed, and intimidated others. His conversion began when monks showed him mercy instead of retaliation.

Monastic life did not erase temptation. Moses battled anger and lust daily. He chose humility—confessing struggles openly and refusing to despair.

When violence returned to claim him, Moses chose non-resistance, embodying “Those who take the sword shall perish by the sword” (Matthew 26:52).

His life shows that repentance does not erase consequences—but it redeems the soul.

St. Bartolo Longo

Occult Practices, Spiritual Terror, and Despair → Light Through the Rosary

Bartolo Longo’s fall into sin was deliberate and intellectual. As a young law student in 19th-century Italy, he became convinced that Catholicism was outdated and naïve. Drawn to spiritualism, séances, and occult philosophy, Bartolo eventually went so far as to be ordained as a satanic priest, publicly mocking Christianity and leading others away from the faith.

What Bartolo sought was power, certainty, and hidden knowledge. What he found instead was spiritual terror. He became plagued by paranoia, interior voices, depression, and intense fear of damnation. His nights were filled with dread; his days with despair. He later admitted that he seriously contemplated suicide, believing his soul was irreparably lost.

Bartolo’s conversion did not begin with confidence, but with fear and exhaustion. Through the patient guidance of faithful Catholics—especially a Dominican priest—he was encouraged to pray the Rosary, even when he felt unworthy or insincere. That simple prayer became a lifeline.

His return to the Church was slow and humiliating. Bartolo had to publicly renounce his past errors, confess grave sins, and rebuild trust. Even after conversion, he struggled with scrupulosity and lingering fear. Healing came gradually through repetition, devotion, and service, not emotional relief.

Bartolo dedicated the rest of his life to promoting the Rosary and works of mercy, eventually founding what became the Shrine of Our Lady of Pompeii. His favorite phrase summed up his theology of hope:

“Whoever spreads the Rosary is saved.”

His life proclaims a hard truth and a hopeful one: even deliberate spiritual rebellion can be healed—but humility and perseverance are required.

St. Margaret of Cortona

Sexual Sin, Dependency, and Pride → Public Repentance and Reparative Love

Margaret of Cortona’s sin was not momentary—it was sustained and socially visible. As a young woman, she became the mistress of a wealthy nobleman, living in luxury outside of marriage. Her identity became wrapped up in status, comfort, and emotional dependency. Though baptized, she ignored the moral life of the Church and resisted calls to repentance.

Her conversion began violently and publicly. When her lover failed to return home, Margaret searched for him—only to discover his murdered body. Standing before death, abandonment, and disgrace, she realized that everything she relied on had collapsed.

Unlike many dramatic conversions, Margaret’s repentance was not instantly consoling. She was rejected by her family, scorned by society, and forced into poverty. She returned to her hometown with her illegitimate child, facing shame she could not escape.

Margaret embraced penance not as self-hatred, but as reordering love. She joined the Third Order of St. Francis, committed herself to prayer, fasting, and care for the poor, and spent years battling temptation, guilt, and emotional instability.

Her holiness was forged through reparative love—loving precisely where she had once misused love. Over time, Margaret became known for compassion toward sinners, the sick, and the abandoned.

Her life teaches us that repentance does not erase consequences—but God transforms consequences into mercy.

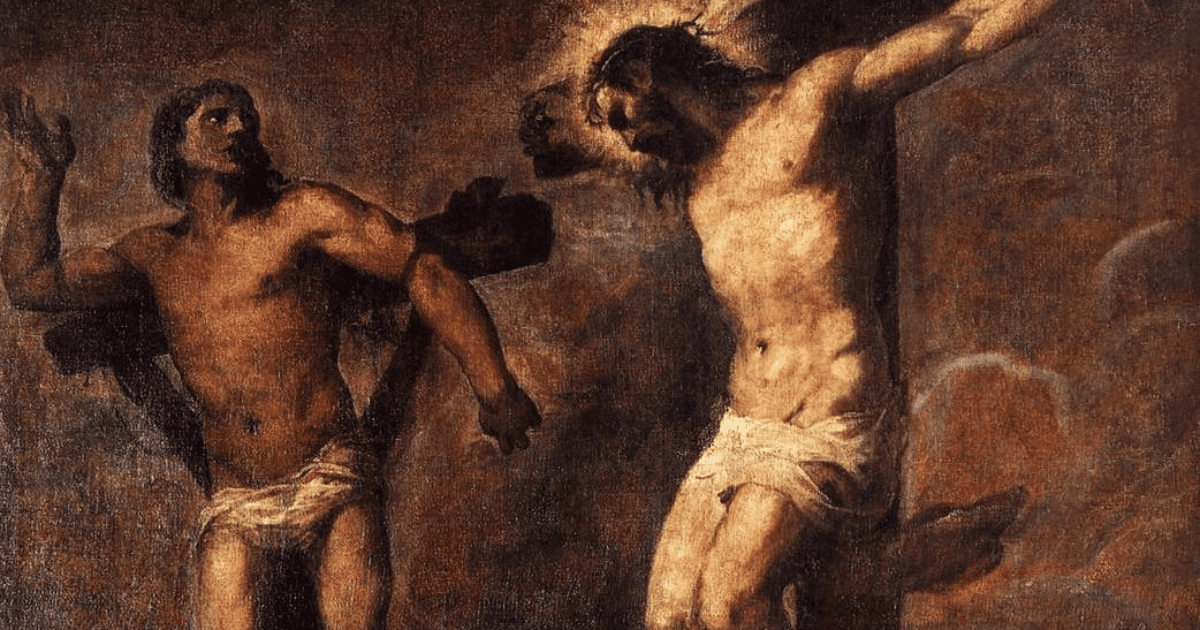

St. Dismas

A Life of Crime and Violence → One Moment of Honest Faith

Dismas’ story is brief in Scripture—but devastating in meaning. Crucifixion was reserved for the most dangerous criminals, suggesting a life marked by theft, violence, and repeated wrongdoing. Dismas was not an accidental offender; he lived outside the law and knew the cost.

As he hung dying beside Jesus, Dismas did something rare: he stopped justifying himself. While others mocked Christ, Dismas acknowledged both his guilt and Jesus’ innocence:

“We have been condemned justly… but this man has done nothing wrong.”

This was his conversion moment—not self-pity, not bargaining, but truth.

With no opportunity to repair damage, make restitution, or prove sincerity, Dismas offered only trust:

“Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

Jesus’ response—“Today you will be with me in paradise”—shatters every false idea that salvation must be earned through visible success. Dismas shows us that repentance is not about time left, but honesty given.

His life testifies that even a single moment of humility can open eternity.

What These Lives Teach Us

- Sin can be habitual and serious

- Conversion may be humiliating and incomplete

- Grace works through perseverance

- God does not demand perfection—only surrender

The Invitation Still Stands

The saints were not holy because they avoided sin.

They were holy because they stopped defending it.

Scripture still calls: “Return to me with your whole heart” (Joel 2:12).

From sinners to saints, the road remains open.

Grace is still at work.

Additional Resources

Read more about the saints on our blog: